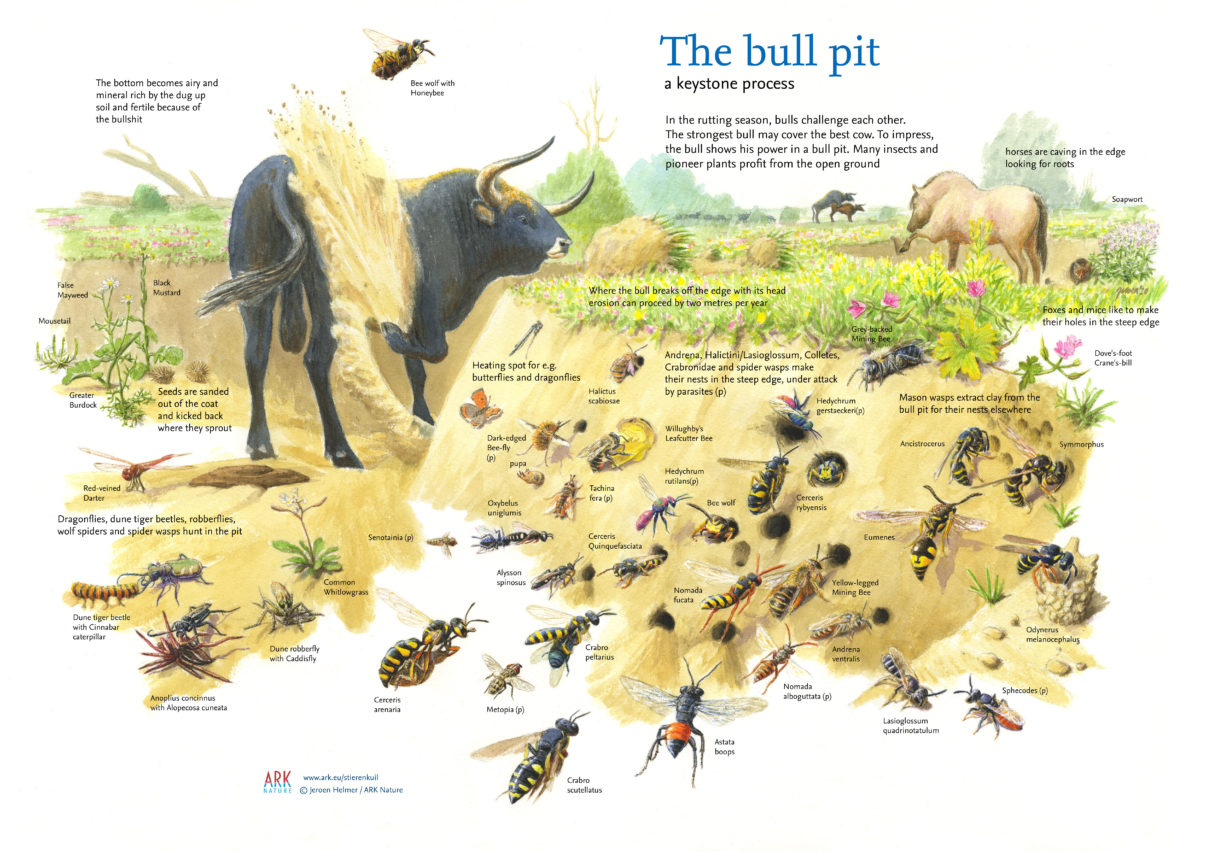

About a thousand years ago, large, wild herbivores started to disappear from Europe. Hunting, poaching and loss of biotope led to their decline. And with the vanishing of those large animals, their behaviour and its influence on the environment stopped too. Not only their grazing behaviour and its effect on vegetation but also the wallowing, rooting and digging. As for the last one, wild bulls used to dig pits in the rutting season to impress the opponents and the cows. As it appears now, these pits were hotspots for pioneer plants and insects.

The return of the bullpit

Bullpits were gone for almost a millennium. Simply because bulls have no competitors on the farm. Now, these pits are coming back in nature. 35 years ago, free-roaming herds of cattle were released at the Slikken van Flakkee and the Imbos in the Netherlands. Since then, year-round grazing with natural herds of horses and cattle has become common practice in natural areas. In the rutting season, bulls exhibit their digging behaviour again. In 2018, ARK Nature, together with Wageningen University and Hogeschool van Hall Larenstein, started to investigate the influence of bull pit dynamics on ground-nesting insects and plants in the floodplain of the river Waal, near Nijmegen.

Rivalry in the rutting season

At the beginning of spring, roaming, mature bulls give up their seclusion and start seeking cows. The strongest and biggest bull can mate the best cow. To determine which bull is best, adult bulls compete. The classical encounter is the head-to-head showdown, but this is very risky. A bull may win the fight, but can also be severely injured by its opponent’s sharp horns. So it is best for the bull to show his strength from a distance.

Bulls can moo for example. The lower and heavier the moo, the more testosterone and strength. Also, bulls will stand next to each other, head next to the tail of the opponent. This is a frozen fight. The bulls will check each other out – the first one to leave has acknowledged the superiority of the other.

Pit sessions

Another way to show strength is to scrape the ground. Sand and dust is thrown up by the foreleg and covers the bull. This really looks impressive. If this is done against a slope, the bull may return to the same spot, time after time. The pit gets deeper and will eventually form a c-shaped, 70-centimetre high pit wall at the slope side. The bull will not only scrape but also sand his fur, exercise his neck muscles and test his horns in the pit wall.

These “pit sessions” take about two to three minutes and typically occur once every two to three days. The sessions continue into September, sometimes even October. When it is too hot, the bulls may even have a break for a few weeks, resuming when the first rain falls. The erosion of the pits can sometimes develop by up to two metres a year, but typically it is by 20 to 30 centimetres in the centre of the pit wall.

The profiteers

The bull will defecate every time he starts scraping in the pit, thereby making the local soil very fertile. There are a lot of plant seeds in the poo that will germinate easily in the dung, mixed with the scraped sand. Other seeds are sanded out of the fur of the bull during the pit session and kicked backwards to the edge of the pit. Pioneer plants, especially, profit from this dynamic situation. Tansy is common, as is false mayweed, common whitlowgrass, black mustard and greater burdock. And more special: soapwort, mousetail, keel-fruited cornsalad and prostrate speedwell.

In the winter, especially, wild horses will scrape the top of the pitwall, searching for roots. In the pitwall, all kinds of animals may dig their holes. It is a great opportunity for mammals, for example, as they don’t have to dig down first. Mouse, rabbit and fox holes are typically found here, with the hole of the latter once even acquired by a common shelduck. Even a bee-eater has been seen successfully breeding in a bullpit in the west of the Netherlands. Arctosa cinerea, a very rare, large spider of gravel plains, can be found hibernating (from October-March) in the insect nests found in the walls of different bullpits.

The bullpit insects

Grasshoppers, all kinds of flies, butterflies and dragonflies are attracted to bullpits to warm themselves, for the average pit is almost 5 degrees warmer than the surrounding environment. The bullpit is also a hunting area for dragonflies, robberflies, dune tiger beetles, spiders and spider wasps. Males of the European beewolf pass the night in some pits in huge numbers. Up to 2000 holes per pit are no exception.

Another group of insects come to collect clay for their nests: mason wasps and bees. Some, like the Eumenes wasps, build their nests completely with this cement. Others, like Symmorphus or Tripoxylon, compartmentalise the hollow stems of dead plants to make breeding cells. Large scissor bees take the clay to close their nests in the tunnels of wood beetles in dead wood.

The pit wall is an excellent place to collect clay, for the insects can – if danger appears – flee easily with their heavy load.

The most intriguing visitors are the ground-nesting bees and wasps. In six pits, 66 species are found, of which 55 species are breeding. The larvae of these insects often need a full year underground to develop into adults. But with bulls regularly returning, how do they survive the bullpit dynamics? To cope with this, most ground-nesting insects dig tunnels of about half a metre, and sometimes up to one metre. Still, the most common wasp in the pits, Cerceris rybyensis, only digs 15 centimetre-deep holes. This one goes for risk spreading, apparently.

A risky business

The bees and wasps suffer from parasites like bee flies, Sarcophaga, Nomada and Sphecodes. The bees and wasps have great strategies to avoid these parasites. Picking a bullpit is one of them. Though risky, the rubbing activity of the bull will shut the entrances to all the insect nests, including the ones with broods inside, rendering them undetectable.

Bulls in areas with clay in the soil produce bullpits with particularly steep pit walls. It seems that in sandy areas the pit walls are less steep and thus less attractive to insects. Further investigation of this phenomenon is needed, but it is clear that bullpits in floodplains are quite rich.

Stimulating natural processes

ARK Nature is stimulating natural processes, such as erosion and sedimentation, ebb and flow, grazing and predation. These are primal forces that have kept the game of nature moving for millions of years. As a result, the players have developed survival strategies that have made them what they are. Bull pit dynamics are such a process. The tossing plays a key role in opening dense vegetation for any animal or plant waiting for this great opportunity.

Jeroen Helmer, Ecological illustrator at ARK Nature